How to get evicted when you’re not being evicted.

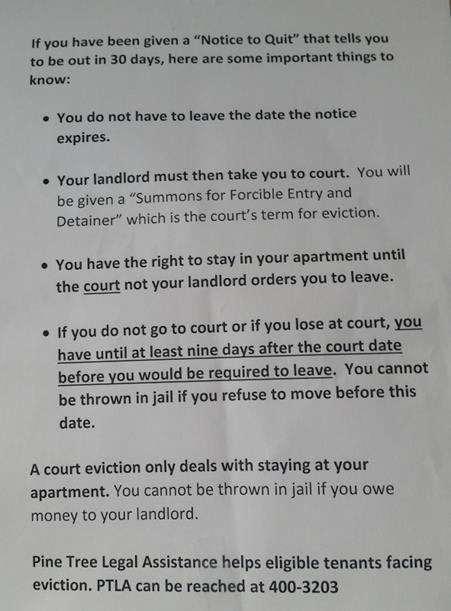

The flyer pictured here showed up mysteriously on doors of a Portland rental property late last week. With no letterhead, logos, signature or any identifying information as to the author, it’s hard to tell who posted these, but given the content it seems it’s from a person or group that thinks they’re helping the tenants that live there, and though it likely springs from good intentions, the advice it contains is dangerous and following it may put tenants in a much worse situation.

following it may put tenants in a much worse situation.

The flyer speaks to tenants who have received a Notice to Quit; in legal terms, that’s the notice that a tenant receives when the lease has expired, when lease terms have been broken, or when the lease is being terminated. A Notice to Quit is not an eviction notice; a Notice to Quit is a notice from a landlord to a tenant indicating that the lease is over and the tenant has to move out within a certain number of days (usually 7 or 30, depending on the circumstances).

If a tenant does not move out of a rental unit within the time given in an Notice to Quit, then the landlord can, and usually will, file an eviction case with the court to start the eviction process. Until the landlord files the eviction (Forcible Entry and Detainer) case with the court, it is still not an eviction.

That inevitably brings up the question, “What’s the difference? If I can’t live there and I have to move out, what does it matter if it’s an eviction or not?” There are major differences, which have a significant negative impact on a renter’s ability to find a new home:

-

Eviction proceedings are a matter of public record. Once the case is filed with the court, there’s a permanent public record, available to and searchable by anyone, of your eviction case.

-

An eviction will prevent you from getting new housing. Most property management companies and landlords won’t rent to tenants who have been evicted in the past. Since an eviction is a matter of public record, it’s easy to find out if a tenant has been evicted – and trying to cover that up by lying on a rental application may subject you to eviction on that basis.

-

Evictions affect your ability to get public assistance.

Public assistance providers have tenant screening criteria and eligibility rules, nearly all of which have prohibitions against giving benefits to tenants with prior evictions. An eviction can terminate your benefits and prevent you from receiving any further assistance.If you’re a tenant, whether or not you’re receiving public assistance to pay your rent, it’s in your best interests to avoid being evicted. When you receive a Notice to Quit, it’s not an eviction until the landlord files a case with the court. Until that point when the case is filed, it’s simply a lease that’s been terminated and you’re free to walk away without a blemish on your rental record. But for tenants that refuse to move after receiving a Notice to Quit, as this flyer is encouraging, the consequences can be harsh. Technically, the flyer is correct when it states that tenants have at least nine days after the court date before they are forcibly removed; the court will wait seven days after the hearing to issue the eviction order, and once served a tenant has 48 hours to be out. But, these nine or so days do not come free, and staying in your apartment and forcing your landlord to evict you comes with a very steep price:

-

Your landlord can charge you rent for the days you stay in the apartment past the move-out date listed on the Notice to Quit. Though a landlord can’t force you out during that time, he or she is not required to let you stay those nine or so days for free. A landlord can deduct that rent from your security deposit, meaning you have that much less to take with you when you look for your next home. And if you don’t have a security deposit, or it’s not enough to cover the rent owed, you could be sued by your landlord for the difference.

- You will be ordered to pay your landlord’s costs for evicting you. Maine law on evictions allows a landlord to recover – from the tenant – his or her costs incurred in evicting the tenant. The end result? You will be paying your landlord to evict you. The filing fee for an eviction case is $75.00, service by a Sheriff runs anywhere from $35 to $75 or more, and there could be additional costs. You will be ordered by the court to pay these costs to the landlord within a short period of time after the eviction hearing, adding even more financial stress to a move. Failure to obey that court order is considered contempt, which can result in additional costs, fines and potentially even jail time.

- You can be forcibly removed by the Sheriff. If you do not move out by the deadline listed in the Notice to Quit or within a week after the court date, you’ll be served by the Sheriff with a notice giving you 48 hours to be out of the property. If you still don’t move, once those 48 hours are up the Sheriff can physically and forcibly remove you and your belongings from the premises – and don’t expect white glove moving services, they simply remove you and your things from the property.

So while some of the things stated in that flyer are factually accurate, following the advice contained therein can result in significant additional expense to the tenant, unnecessary eviction proceedings and major hurdles to overcome in finding future housing. If you have received a Notice to Quit, whether at the property where these showed up or elsewhere, contact an attorney and get advice that fits you and your situation.